From A to Z (Assault to Zofia), Part 1: Lee Miller

Self portrait with sphinxes, Lee Miller Vogue Studio, London 1940

Since I was violently assaulted almost exactly a year ago (Christmas Eve, 2024) at my local village pub and had two of my front teeth knocked out, I have found myself to be more wary of the world. My increased social anxiety is still most acute in my immediate local area. And when my last romantic relationship ended in August of that year also, and it became clear that my once-wide social circle had diminished almost completely, my resulting solitude fed into a sense of alienation which in turn, and especially since my assault, compounds my isolation and general social anxiety in an unhelpful feedback loop.

So, although a day-trip to London to visit a few exhibitions, galleries, and museums was a favoured treat for myself and my partner, or something I previously would not have thought twice about doing on my own, it is not something I had embarked upon in the past couple of years. Having been out of work for a few months had decimated my finances also which hadn’t helped my engagement with the wider world. However, it was a metaphorical horse which I knew I had to get back on if I were to get where I wanted to go. After a little online research at the end of the previous week, I resolved to spend Monday 22nd December in London with three galleries in mind, taking in selected exhibitions across the venues.

Tate Britain had a retrospective of Lee Miller’s photography, The National Portrait Gallery had its annual exhibition of the Taylor Wessing (photographic) Portrait Prize entrants, and the Photographer’s Gallery, which is always worth visiting, had amongst other exhibitions a fascinating exhibit celebrating 100 years since the invention of the automatic photo booth, and a curious and personally relevant collection by Zofia Rydet documenting the domestic lives of simple Polish people and their homes through the 70’s and 80’s.

I was familiar with some of Lee Millers output, more so her surrealist photography and collaborations with Man Ray. And while I was aware of her wider body of work - for example, from her time as a war correspondent documenting moments from the second world war and its aftermath - I had not had much exposure to the full scope or seen it in person.

Being mindful of staying focussed on artists and exhibitions that are relevant to my own practice and research, there are numerous reasons why Lee Miller’s catalogue was of interest to me. Firstly, and perhaps most obviously is the surrealism; the explicit notion that despite bending reality and disrupting norms of visual representation one can still nevertheless present “truths” and meaning, albeit sometimes those which are seated in the unconscious mind, beneath the surface of rationality.

With the surrealist art movement being heavily influenced by Freudian theory, it was no surprise to see numerous references to “the uncanny” in the text accompanying Miller’s surrealist works, especially as some of the images embodied a transgressive eroticism which is an important aspect of Freud’s exploration of the uncanny in terms of repressed sexual desire and the Oedipus complex.

Secondly, the fact that Miller was always keen to explore new technologies and processes to expand her range of expressive tools strikes a chord with my own approach of digitally manipulating my images. And interestingly, it is probably also the case that the work of the surrealist photographers like Miller who were creating their images at a time when photography was yet to be fully embraced as a “fine art” form, were probably partly responsible for elevating the form above the purely representational and documentary.

Thirdly, Miller like myself, often used herself as a subject in her sometimes experimental, surreal images. She already developed a complex relationship with the camera/photographer having modelled as a child for her father and later as a professional fashion model before switching sides to possess the gaze herself, not just be gazed upon. But also I know from my own experience how much lower the stakes are, how much easier it is to experiment and risk getting things wrong (sometimes for the better), when one is shooting oneself and not needing to worry about managing the dynamic of an “other” subject.

Finally, being preoccupied as I am with an egalitarian position on the sexes, I always take pleasure from engaging in and acknowledging the work of women when, as is too often the case, it has not received due credit; the credit the work would have received had the artist been male. But beyond this, I also think that our culture suffers if it does not more fully, more proportionally reflect humanity, including the female position and the female view as presented by their art. I had suspected it anyway, but it was still disappointingly unsurprising to discover at the exhibition that sometimes Miller’s work had previously been attributed to, or appropriated by her male artistic collaborators, or that her contribution to collaborations was sometimes diminished or uncredited. As is said, it is the victors that write the history. Until more enlightened times at least.

And indeed, my inclination of the relevance to my practice was vindicated by attending the exhibition where I was rewarded with a sense of affinity and alignment with Miller and some of her work. Now of course, I don’t doubt that my Reticular Activating System (the function of the brain that amongst other things seeks information that confirms one’s beliefs) was significant in helping me identify these occurrences, but I could not help but notice the repeating motif of usually dismembered or damaged statues and mannequins. This extended to the looped screening in one room of Jean Cocteau’s Pygmalion-esque film, The Blood of a Poet, in which Miller herself plays the role of an armless statue and muse.

I took this theme which recurs throughout her work as both photographer and model/actress to reference and echo the experiences of being objectified by the camera and the inherent relinquishing of authorship over the self that this entails. Even in the images she makes of herself and her own body or collaborates with male artists to produce, which sometimes also depict the body as a sensuous art object, or erotic sex object, there is a sense of greater agency (than in her commercial, objectifying modelling) and transgression from the power dynamic of the status quo; seemingly a more empowered self-expression and claim staked for her own erotic interior world.

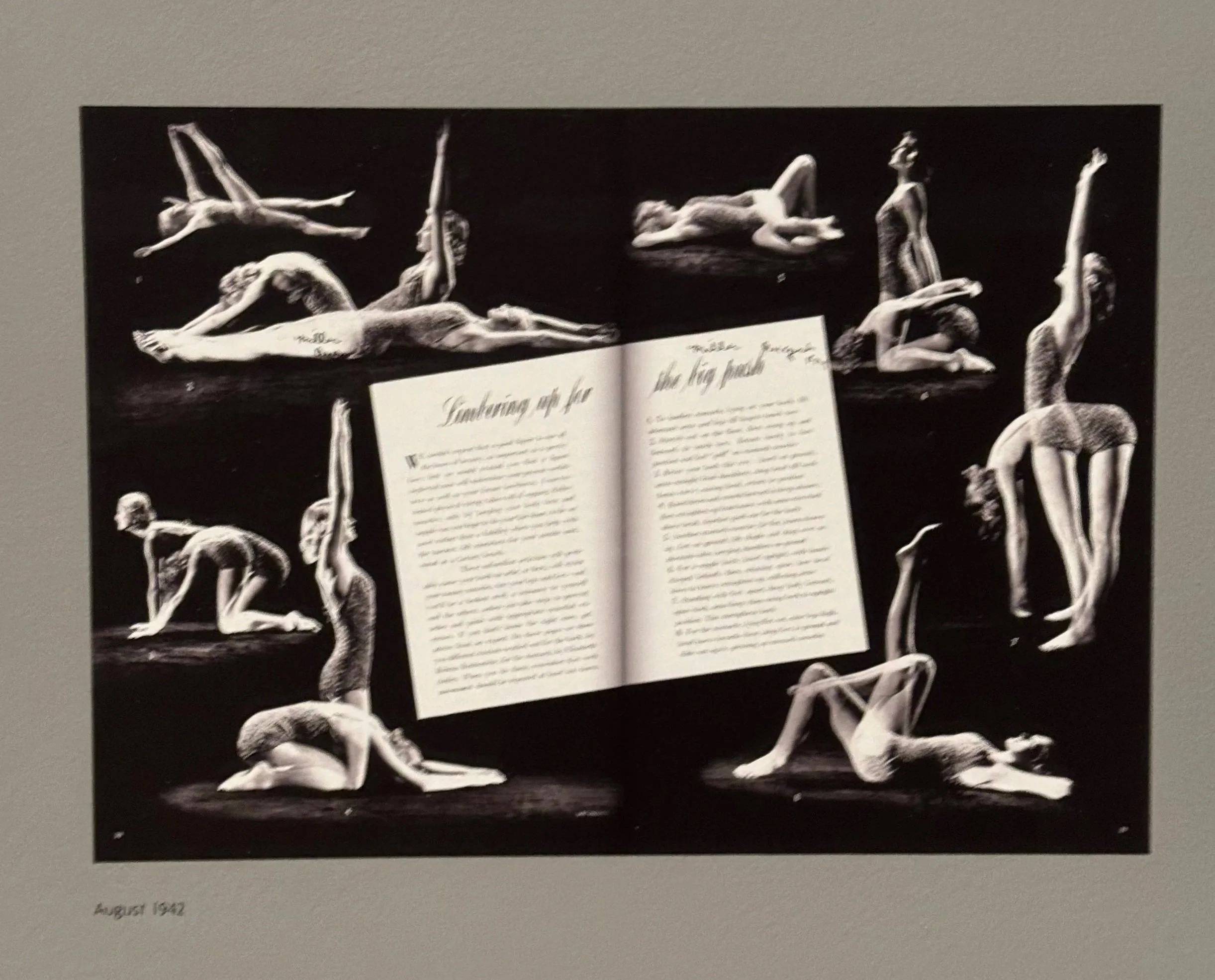

Beyond her more experimental and surreal images, highlights of the show for me were examples of her own fashion photography, which in the early forty’s included spreads from Vogue showcasing various non-representational techniques such as photomontage and solarisation (a darkroom technique producing a bizarre metallic affect) which she jointly innovated and developed (excuse the pun) with Man Ray, himself an icon of surrealist photography who had previously been her mentor then artistic collaborator. Other Vogue shoots of hers employed surreal compositions and staging such as the inclusion of stuffed big-game animals from the reserves of Africa and other unusual props.

Limbering up for the big push, Lee Miller, Vogue, 1942

I also enjoyed some of the quirky portraits she’d made of (famous and significant) artist friends, but found some of her images from the end of the second world war more interesting, especially the portraits of the female pilots and aviation technicians which revealed to me something I was not so cognisant of before.

Ultimately, it was a genuine pleasure to immerse myself in the work of a photographer whom I’ve been aware of, admired, and inspired-by for pretty much my whole photographic life (getting on for 35 years now), but who’s images I had only seen in books and too few at that. Well worth the visit.

As evidence of the fact that I was out of practice in planning the itinerary of a day-trip for gallery visits, I found when arriving at Tate Britain to see the Lee Miller Exhibition that I’d made a stupid mistake when making arrangements late in the evening a couple of days previously.

On considering the locations of the three galleries that I intended to visit, I had decided to visit Tate Britain first (being my furthest destination), taking the Victoria line south towards Brixton, alighting at Pimlico then travelling on foot to the Tate. Once finished there, I would walk along the Thames, first on the north side, then on the south side, nearly up to the Royal Festival Hall before crossing back over the river on the Hungerford/Royal Jubilee rail and pedestrian bridge (which provides superb views back down the river).

Back on the north side of the river, it would only be a short walk to Trafalgar Square and just beyond that, the National Portrait Gallery. From there I could walk through Leicester Square, China Town, and Soho to the southern end of the pedestrianised Ramillies Street where the Photographer’s Gallery is situated. The north end of Ramillies Street leads via some steps onto Oxford Street, only a few minutes walk from Oxford Circus. Then it’s only a short journey north on the Victoria Line back to Kings Cross, hopefully in time for one of the late-afternoon off-peak trains. Not only are the peak-time trains significantly more expensive, but they are usually also overcrowded and too many times in the past when forced to travel on this service I’d had to stand or sit on the floor for at least half the journey until sufficient people had spilled out of the train at their destination stations.

However, the flaw had not been in my route planning, but in my timings and ticket booking. Both Tate Britain and the National Portrait Gallery recommended on their respective websites to book tickets in advance for a particular time-slot, thus avoiding a wait if exhibitions were at capacity. I don’t usually worry too much about doing this as generally I avoid visiting London for such trips at the weekend when the city is fullest of leisure and pleasure seekers, but despite my trip being a Monday, it was also now the Christmas Holidays for schools and therefore some adults who would have booked corresponding time off. Additionally, I would essentially have only half a day to actually complete my itinerary as using the convenient off-peak trains meant I would arrive at Kings Cross shortly after mid-day and need to travel back before four-thirty.

My logic then was to book a ticket for the furthest and first exhibition I would visit, allowing time and a little leeway to walk from the tube station to the gallery, hoping as it were to hit the ground running so I was not too harried later if I had to wait to gain entry or was delayed on route (I was taking a camera and a couple of lenses for impromptu photographic opportunities). Somehow though I had in error managed to book a ticket for the National Portrait Gallery to see the Taylor Wessing Portrait Prize at the time I had wanted to be visiting the Lee Miller show at Tate Britain! It was, late, I’d had a couple of glasses of wine…

I therefore had to laugh at myself when expecting hassle-free admittance, the confused employee at Tate Britain pointed out that the PDF booking confirmation I was showing him on my phone was in fact for a different exhibition at an entirely different gallery! Fortunately, after apologising for my error, he was able to sell me a ticket and admit me to the Lee Miller exhibition without delay. I hoped that NPG could be equally flexible – although tickets to the Taylor Wessing show weren’t too pricey at under £10, unlike the Cecil Beaton exhibition hosted there simultaneously which I would also have like to have seen, but at £23 for entry and being less relevant to my current practice, I hadn’t been able to justify.