Balancing Act

Early balance sculpture March 2017

An initial response to reading the first chapters of Making by Anthropologist Tim Ingold

Having already been inspired by Shaun McNiFF’s argument for the value in Arts Based Research from my prior reading, beginning Tim Ingold’s book Making only served to catalyse and crystallise my thought process.

As metaphorical pennies continued to drop while reading Ingold, an idea formed in my mind: I had already experienced a most simple and perfect example of his proposal that certain knowledge could only be achieved by immersive experience in the process of making. That only by corresponding with the materials of certain subjects/objects can knowledge about them be successfully elicited.

I first tried the art of stone balancing a few years ago. If recollection serves me right, it was a journey inspired by a serendipitous encounter with images or a video of balance sculptures served up to me via social media. These beautiful, often improbable forms of stacked stones, large and small, resonated strongly with me. They reminded me of Alexander Calder’s Mobiles but also times when in nature I had encountered occurrences of boulders falling to rest in unlikely, apparently precarious ways.

Family of Four March 2017

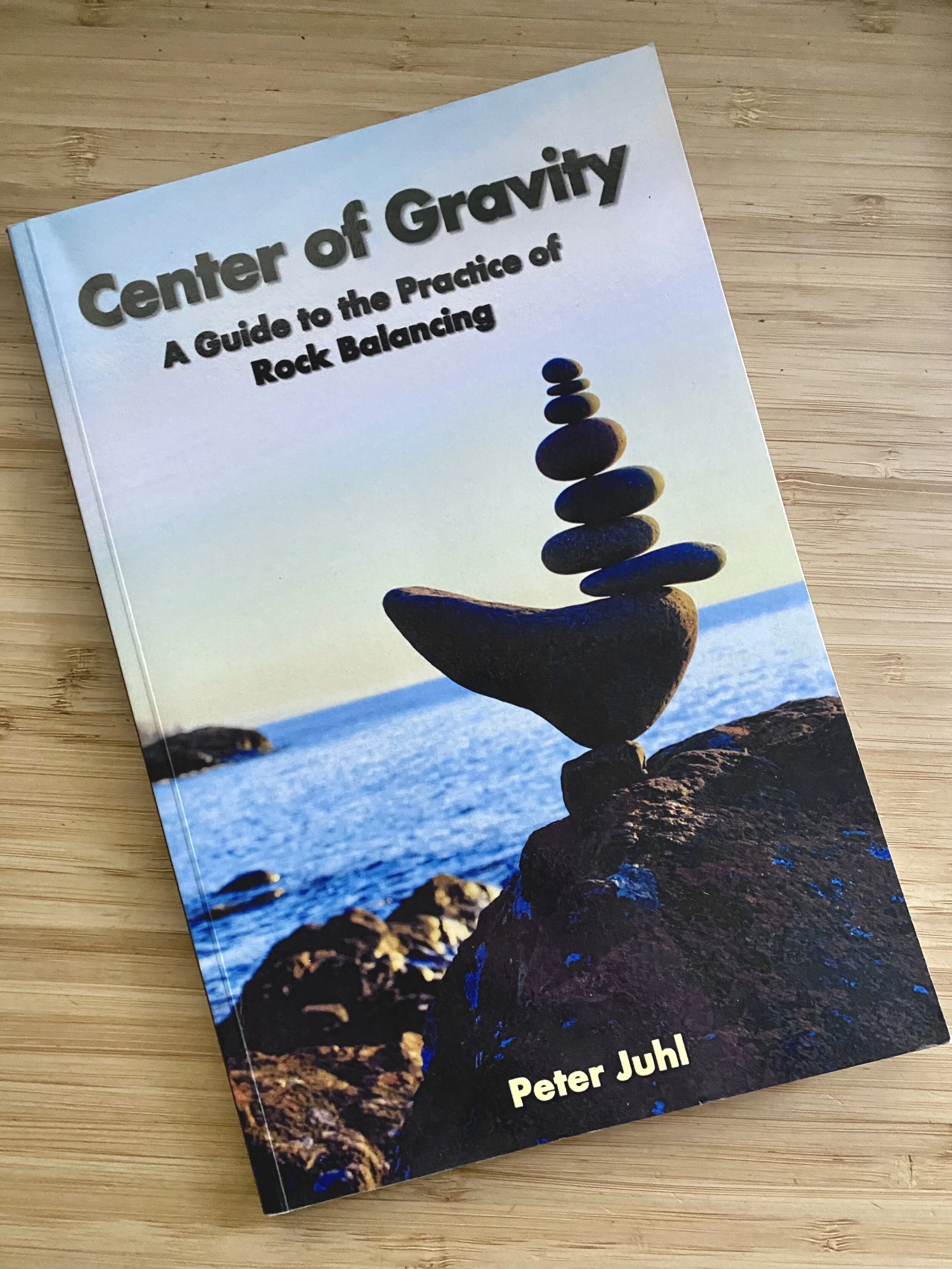

While my preference would have been to explore this naïve art form with stones and boulders, in their natural environment of rugged coastlines, moors and mountains, my situation at the time was not conducive to such adventures. However, a trip to my local garden centre was fruitful in that for £40 I acquired a selection of stones of different composition, colour, texture, size, shape and weight. Complementing these raw materials with a simple little book called Center of Gravity, I could at least begin to play and be further inspired by the writing, photographs and illustrations I now had to hand.

Center of Gravity: A guide to the Practice of Rock Balancing by Peter Juhl

The book provided guidance on the principles of the practice but, of course, each stone was completely unique and it was only by trying myself to balance one atop another that I could discover how two or more stones could interact to create my own beautiful (to my eye at least) balance sculptures. Indeed, given the sheer complexity and number of variables at play it is hard to imagine that a sufficiently sophisticated formula or computer algorithm could ever be written to substitute for the practice of finding by placing, carefully by hand, the forms I created through my own attempts at doing.

I’d intentionally chosen stones with a variety of compositions, some were harder and smoother, apparently comprised of layers, others were rougher and softer, more granular in their texture. I could only guess at how these differences, along with size and shape would manifest in trying to balance the stones. And it was in the simple process of placing one stone atop another and testing for balance by only slightly relieving the support my hands offered, then repositioning until finally balance was found, that I experienced a visceral thrill in making I had not felt for a long time. Movements of only a millimetre or a degree, could be the difference between balance and imbalance.

Then of course further complexity arises as a third stone is added and begins to act with the materials, forces and phenomenon of stone, gravity and balance. Whilst practice did allow me to improve my intuition of how to successfully balance the stones, it is not conceivable that there is a way of knowing what balanced forms are possible with any given set of stones without actually putting one’s hands on the materials and finding the path to balance within them and by corresponding with them.

This then is why this seemingly simple practice of stacking stones seemed like the perfect illustration of the value in Arts Based Research; in the process of knowing by doing. We can know, scientifically and mathematically all sorts of things about the composition of different stones, of the law of gravity and about the phenomenon of balance. However, the only way to truly “know” how a few rocks can balance improbably together is by the practice of attempting to balance them.

XSK October 2020

Interestingly, it was also this experience I’d already had in knowing by doing that allowed me to find accord in and fully know the truth in Ingold’s and McNiff’s arguments. I was fortunate that my prior experience meant that what they were positing was not just a theoretical or even ideological argument but in fact an undeniable truth.

The majority of my previous artistic practice was undertaken prior to my experiments with creating balance sculptures and also prior to reading Ingold and McNiff. I had known there was value in my practice as a way of knowing, but not before now had I had such a clear understanding of how beautiful and simple the process was: take up my materials, take on the acting forces, feel them, listen to them, move with them, follow them, correspond with them…

XSK October 2020

…what is created will be the truest expression of material, force, phenomena and maker in correspondence and will produce knowledge that is unknowable by any other means.